By Matt Vogel, Associate Professor, School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany, State University of New York; and Anne Trolard, MPH, Manager, Public Health Data & Training Center at the Institute for Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis

This blog is part of a special series by the Harris Institute’s Gun Violence and Human Rights Initiative and the Institute for Public Health’s Gun Violence Initiative in recognition of National Gun Violence Awareness Month, launched on June 5th for Gun Violence Awareness Day. Throughout this series we highlight the work being done on this critical issue across campus, the St. Louis region, and the country.

The killing of George Floyd—yet another unarmed black man—by police in Minneapolis and the ensuing global protests have pushed the conversation around issues of race, inequality, and policing to the forefront in America.

A large part of this dialogue has centered on redistributing funds away from police departments and into community-based solutions. Supporters point to the glutted coffers from which municipal departments pull funds, often to the detriment of other community services (e.g., mental health, social welfare). Shifting monies might be an important step towards investment in community alternatives that could prevent violent conduct before it occurs. Detractors point to the obvious public safety costs that would accompany divestment, especially in the short term. After all, if the police aren’t around, how will communities prevent and respond to violent crime?

In this blog post, we highlight some of the ongoing violence prevention efforts in the city of St. Louis. We draw attention to police-community partnerships and environmental crime prevention efforts that serve as a middle ground between those calling for abolition, on the one hand, and those pushing for business-as-usual approaches to policing, on the other. In St. Louis these partnerships are coordinated by the St. Louis Area Violence Prevention Commission (STLVPC), which brings together over 100 organizations to lead a coordinated strategy for violence prevention. They also emphasize trauma awareness and racial equity across the board. The safety of our community relies on a well-trained police force operating in tandem with community organizations to prevent violence. Investing in these types of partnerships, and their coordination, provides a promising path forward.

Let us begin with a few straightforward observations: First, violence in not evenly distributed across our cities and towns, or even our neighborhoods. Crime rates vary substantially from neighborhood to neighborhood, even from street to street within the same neighborhood. This variation is intricately linked to the socioeconomic composition of an area and features of the local built environment. Identifying the environmental risk-factors that increase the risk of criminal violence is a cornerstone to designing effective public health interventions.

Identifying high-risk areas, however, is not as easy as it seems. The US Department of Justice estimates that over half of all violence goes unreported to local law enforcement. Thus, any prevention efforts built on official data, such as those collected by municipal law enforcement agencies, are incomplete. Official records are usually accurate when it comes to severe forms of violence (i.e., those resulting in serious bodily injury or death). Minor forms of violence are less likely to come to the attention of law enforcement.

This brings us to our second observation: Serious criminal violence often reflects the culmination of an escalating series of interactions. What may begin as a tiff on social media can quickly escalate into a physical assault, and eventually lead to increasingly serious forms of retaliatory violence. Violence cascades. Upstream interventions present a unique opportunity to prevent escalation. Identifying when, where, and for whom such interventions should be directed is crucial.

How do we proceed? There are two programs in place in St. Louis intended to intervene directly with individuals who face an elevated risk of experiencing retaliatory violence: Life Outside Violence and Cure Violence

Life Outside Violence is a hospital-based violence intervention program targeted at victims of violence who have been hospitalized with penetrating injuries (e.g., knife wounds, gunshot). The program offers case management support to help people identify the steps they need to take to break out of that cycle of violence and has been operating in four area hospitals for almost two years.

Cure Violence is a program that staffs violence interrupters who work on the ground in communities to de-escalate situations between people that would likely lead to injury or death. St. Louis implemented the first phase of its Cure Violence program in the spring of 2020.

Closing the data gap is an important first step in understanding the extent of criminal violence in the City of St. Louis. Currently, the STLVPC is working with the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department and the two major trauma centers to implement a data-sharing agreement known as the “Cardiff Model.” In short, the Cardiff Model was pioneered by Dr. Jonathan Shepherd, a trauma surgeon who lived and worked in Cardiff, Wales. Shepherd suspected that many of the victims of violence treated in his hospital had failed to report their assaults to police. He began collecting a few data points from assault victims about their injury: date and time of injury, exact location, and mechanism or weapon used. He compared these data with police data, and confirmed his hypothesis: The locations of incidents reported to the hospital varied considerably from the official police data.

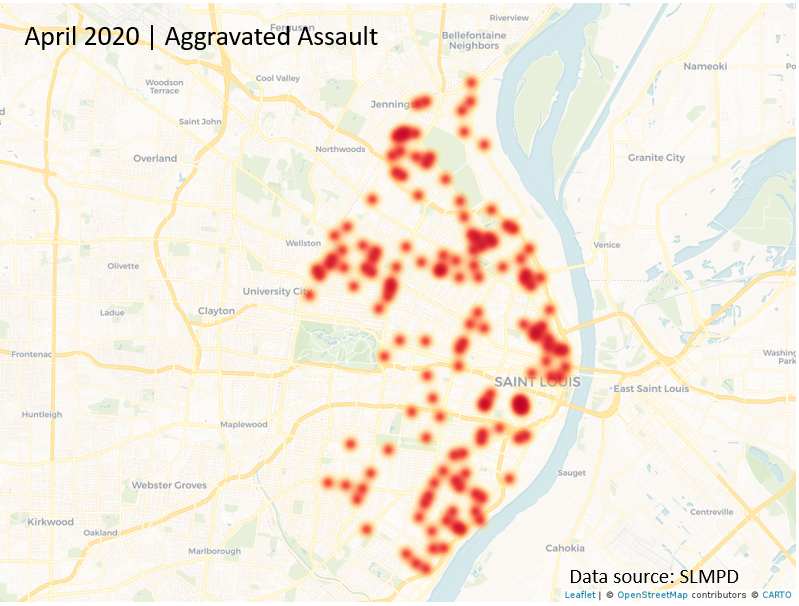

How are we using Cardiff in St. Louis? In an effort to provide a wholistic understanding of the distribution of violence in St. Louis, data collected by hospitals is de-identified, aggregated, and mapped alongside police data. The map below depicts aggravated assaults in the City of St. Louis: the intensity and size of the shading indicates an increasing concentration of assaults.

Members of the STLVPC are working closely with the police and local hospitals to build statistical models that help identify (1) where violent crime tends to cluster and (2) the characteristics of these places that might be rife for environmental interventions. Our preliminary models suggest that features of the built environment—including vacant lots, retail establishments, and ATMs—drive the distribution of violence in St. Louis. Vacancy seems to be a particularly salient driver of interpersonal violence. Environmental remediation strategies, such as the razing of dilapidated properties and the beautification of vacant lots have been effective violence prevention strategies in other major cities. It seems that similar interventions would work well in St. Louis.

At a time when communities are grappling with how to balance safety, justice, and equity for all of their citizens, we advocate for continued support for the St. Louis Area Violence Prevention Commission and its role in supporting a coordinated violence prevention plan—one that is trauma-informed, community-engaged, and striving for equity.