By: Sam Rouse, JD ’22

The Robert H. Jackson Center celebrated the 75th anniversary of the signing of the London Agreement and Charter with a global webinar on The Age of Robert H. Jackson – London, Nuremberg, Today on August 8, 2020. The webinar was co-sponsored by the Case Western Reserve University School of Law, the International Nuremberg Principles Academy, the International Bar Association, and the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute. The webinar, moderated by Professor Michael Scharf, featured experts calling in from the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, as well as Ben Ferencz, the last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor.

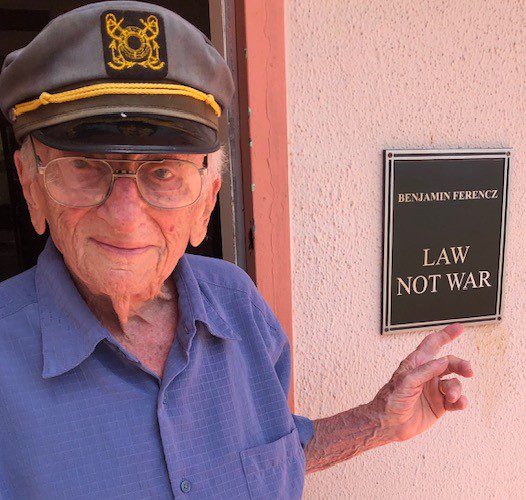

Ben Ferencz opened the webinar by making an impassioned plea for global justice. Drawing not only on his experiences as a prosecutor, but also as a soldier in the European theatre, he has dedicated his life to ensuring that the events of World War Two can never happen again. Progress is being made towards this goal, which, as he said, “is about the best you can hope for.” To achieve this goal requires a shift to thinking in planetary terms, as the next global war has the potential to destroy the entire planet and all of humanity as we know it. Ferencz set the tone for the discussion, stressed that the next generation of legal thinkers can truly achieve the goal of “law not war.”

Professor John Q. Barrett provided an overview of the life of Robert H. Jackson, as well as the London Charter. Barrett explained how Jackson was suitable for his role in drafting the London Charter given his wide range of legal experiences, his leading role in the FDR administration, and the strength of his legal reasoning and writing. Barrett also emphasized how the London Charter was ultimately a choice – a deliberate choice of the path of law rather than war.

David Crane, the founding Chief Prosecutor at the Special Court for Sierra Leone, put the London Charter in historical context. The last 100 years have been the “bloody 20th century,” with well over 200 million humans dying from war, disease, famine, and atrocities. In the midst of this bloodshed, the London Charter stands out as a bright and shining hope. Without the London Charter, it would have been difficult to build the accountability movement in the late 20th century which culminated in the Rome Statute establishing the Permanent International Criminal Court (ICC). Crane explained that the development of accountability can be conceived of as a series of waves crashing against the rocks of impunity. The first wave was the Nuremberg Trials; the second wave being the establishment of the ad-hoc tribunals and the ICC; and the final wave is ongoing and can be characterized by a retreat away from internationalism towards nationalism, with states and NGO’s stepping up to try and address impunity.

Professor Leila Sadat then provided more detail on the American decision to proceed with a trial rather than summary executions following the end of World War Two. She explained that although the United States had not favored legal action against the Kaiser after World War One, the idea of trials had been circulating in the legal community between World War One and World War Two. However, Professor Sadat pointed out that even in the United States the idea of a trial wasn’t uncontentious, with Roosevelt floating the idea of summary executions at Quebec. Following the death of Roosevelt, however, the Truman administration embraced the idea of trials, and chose Jackson to represent the United States as their best legal mind.

James Johnson, Prosecutor at the Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone, reflected on the lessons modern tribunals have learned from Nuremberg, drawing on his experience as a prosecutor. One of the major criticisms of the Nuremberg Tribunal was that it reflected victor’s justice, which Johnson believes has been addressed in modern tribunals with fully international judiciaries looking at all parties to a conflict and providing greater due process protections. A concern that is just as relevant to the modern tribunals surrounds the retroactive punishment of crimes. Although time may have clarified that there exist certain international crimes, the issue of retroactivity still raises its head whenever courts attempt to try new variations of crimes, such as when the Special Court for Sierra Leone was the first court to convict for the crime of using child soldiers.

Mark Ellis, Executive Director of the International Bar Association, traced the development of the London Charter. He noted the key role of the UN War Crimes Commission, both in categorizing the crimes committed, and in assisting Jackson in developing the London Charter and the Nuremberg Tribunal. Ellis also spoke to the importance of the London Charter in establishing universal jurisdiction, which is today being applied more restrictively. Ellis called on the younger generation to pick up the mantle of international justice and be a voice for the victims of atrocities in the 21st century.

Professor William A. Schabas argued that the idea of having a trial, rather than summary executions at the conclusion of the war, really was almost inevitable. Although the British had to be convinced to proceed with trials, the support of Roosevelt, Truman, Stalin, and the UN War Crimes Commission all made it almost certain that they would agree to host trials. Professor Schabas also reflected on the spirit of cooperation which guided the drafters of the London Charter, leading to their success in combining civil and common law concepts, something which the International Criminal Court continues to struggle with today. Schabas also noted that while there were some discussions of creating a permanent court at the time, even culminating in a draft, the International Criminal Court has moved much more slowly than the Nuremberg Tribunal, so it may have been a blessing that the drafters settled on a single tribunal at the time.

(Photo by U.S. Army photographer Ray D’Addario, from the Collections of the Jackson Center)

Navi Pillay, President of the Advisory Council at the International Nuremberg Principles Academy; former UN High Commission for Human Rights; and former judge at the ICC and ICTR, reflected on the legacy of Jackson and his visionary foresight for the modern international criminal courts. Jackson recognized the risks of victor’s justice, removed the defenses of superior orders and state actions, and emphasized the role of the defense. These influences are still felt today, which the ICC addressed by creating a truly international system with the entire world coming together to try and remove any elements of victor’s justice. The removal of the superior orders defense and of acting in the state interest was a landmark action in terms of removing impunity. The ICC has built upon this and created more sophisticated and fairer standards for defendants than were applied at Nuremberg.

Klaus Rackwitz, Director of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy, spoke on the contemporary relevance of the Nuremberg Principles, before explaining the reception of the Nuremberg Tribunal in Germany. Rackwitz argued that the Nuremberg Principles are durable and can easily adapt to modern challenges such as terrorism. He also noted that the Nuremberg Tribunal was generally well received in Germany, with controversy arriving only when cases began to target lower ranked actors.

One of the final points before the webinar closed came from Ben Ferencz. Addressing a question from the audience, he spoke to what motivated him to apply universal jurisdiction. Ferencz explained that his focus wasn’t on legal terms, but on the fact they “were murdering human beings, murdering infants, killing 33,000 people in two days.” He thought in human terms, rather than legal terms, trying to create a system which would protect all people in the future. Ultimately, this is what he asked the judges for during the Einsatzgruppen trial, and an important step towards that goal was given in the judgment.

Reflecting on the legacy of the Nuremberg Trials and their influence on modern trials, it is perhaps symbolic that this event took place virtually. Many speakers spoke of “passing the torch” to a younger generation, and a virtual webinar meant that many of this generation from around the globe could attend this event and hear the inspirational words of Ben Ferencz and others. The webinar can be watched online.