By: Suhao Chen

H.E. Judge Liu Daqun, Appeals Judge and Vice-President of the ICTY and Judge of the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals

On May 25, 1993, in the midst of violent conflict in the Balkans, the UN Security Council decided (through Resolution 827) to establish the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to prosecute persons responsible for serious violations of humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia after January 1, 1991. Almost a quarter century later, the ICTY, in which 161 people have been indicted for international crimes, is expected to close at the end of 2017 with numerous achievements. On February 22, 2017, Washington University School of Law was honored to welcome His Excellency Judge Liu Daqun, Vice-President of the ICTY, who shared his insights on the Tribunal’s legacy and its challenges at this historic point as part of the William C. Jones Lecture Series.

The establishment of the ICTY made it impossible for war criminals in the former Yugoslavia to seek shelter behind arguments of national sovereignty (as of 2011, no fugitives indicted by the Court remain at large). As Judge Liu said at the beginning of his lecture: “the International Tribunal will no longer tolerate impunity of those who committed serious crimes. No matter what position he or she possessed, (he or she) will eventually be prosecuted and put on the trial.” Judge Liu explained that in addition to fighting impunity, the Tribunal has made other important contributions to international criminal justice, both in procedure and in substance. Among them, he highlighted the application of international customary law, the definition of genocide and the adoption of evidence rules. Undoubtedly, apart from its contributions to international criminal law, the ICTY has also impacted the rule of law and accountability in domestic jurisdictions. When domestic courts deal with atrocity crime cases, they can and do look to the ICTY and its jurisprudence for guidance on rules, practices and substantive precedent in international law. Furthermore, the Tribunal has also worked closely with local authorities to assist them in dealing with international crimes and improving their judicial systems to comply with international standards.

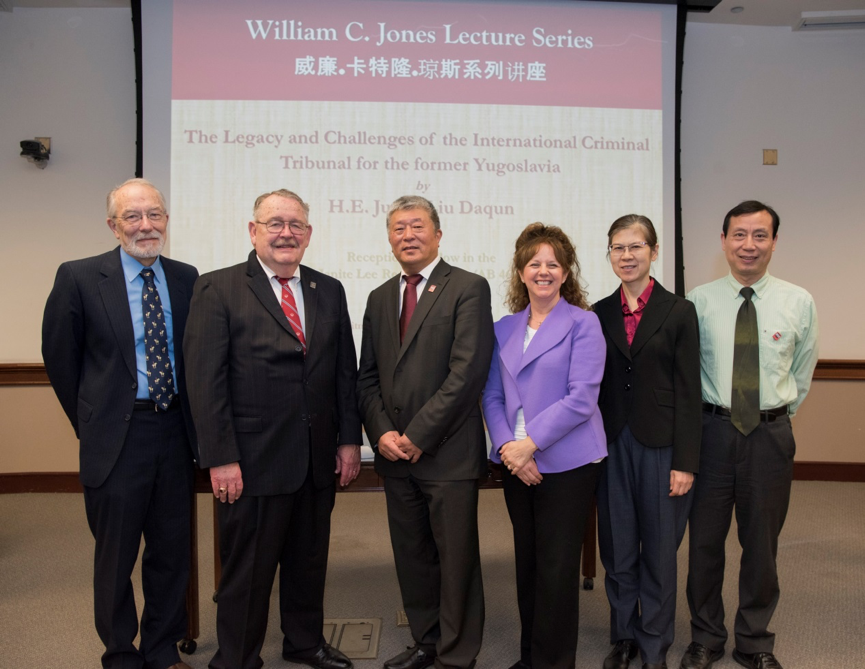

H.E. Judge Liu and his wife, Prof. Yang Lijun, who is a former Washington University Law Visiting Scholar, with Washington University Law and Arts and Sciences faculty

In addition to his presentation of the Tribunal’s legal contributions, Judge Liu’s description of his personal experience as an ICTY judge illustrated the importance of enforceable international criminal and humanitarian laws. In presiding over the Blagojević and Jokić case, for example, Judge Liu and other ICTY judges heard evidence of genocide and crimes against humanity (extermination, murder, persecution, cruel and inhumane treatment, and forcible transfer among other crimes) committed following the fall of the Srebrenica enclave, where between 7,000 and 8,000 Bosnian Muslims were killed by the Serb Army. In all cases, however, a judge’s job is to remain impartial and examine specific links between individuals and the crime. The earlier conviction of Radislav Krstić, a Bosnian Serb Army officer who facilitated the massacre, had resulted in the first genocide conviction at the ICTY and as a conviction against a military leader, made an important statement against impunity. By including impartial findings and detailed facts, judgments in the Blagojević and Jokić and Krstić cases helped not only to clarify what happened in these atrocities on paper, building a historical record, but also engrave them in human history as a permanent reminder.

However, it has to be admitted that the ICTY’s work has also been the subject of criticism, including on its jurisdiction, impartiality and efficiency. For some people, the ICTY is another example of victor’s justice and a tool of Western interest. Thus, it is not surprising to find judgments of the ICTY that have been criticized in certain counties, but embraced by most of the international community. Judge Liu responded to these critiques in his lecture as well, describing how certain judgments were criticized by national governments in the former Yugoslavia. He suggested that governments and people in the region should look seriously at the past and determine whether establishing responsibility for atrocities has been fulfilled by international justice, and that they should recognize the wrongs of the past and look forward to the future. He also noted that some common critiques about the Court result from misconceptions about its mandate. The Court’s purpose is judicial, not political, and it cannot be expected to be solely responsible for maintaining peace and security, though those issues can of course be affected by justice mechanisms.

Chinese law students meet with H.E. Judge Liu Daqun

We are still living in a world full of cruel and violent conflicts. The pursuit for peace has not stopped, nor has the effort to punish and deter genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The close of the ICTY signals the close of an important chapter of international justice, but the unresolved issues and unaccomplished tasks serve as reminders of the challenges that remain for current and future legal professionals (including law students) as well as for the larger international system. Judge Liu, a former Chinese official and diplomat who studied both in Chinese and American law schools, also met with law students from China and encouraged them to embrace the opportunity to develop essential legal skills and prepare for the challenges of the future.

To watch Judge Liu’s full lecture, visit https://lecturecapture.wustl.edu/mediasite/Play/c2852fb2d3bb4b27ae1dc195ad90d4a21d.