By: Lola Awobokun

I had the pleasure of attending International Law Weekend (ILW) 2019 in New York, October 10-12, as a student ambassador of the Harris Institute. The event was jointly sponsored by the International Law Association American Branch (“ABILA”) and International Law Students Association (“ILSA”). The theme was “The Resilience of International Law.”

Introduction

The panel The United States and the International Criminal Court: Challenging Times explored the relationship between the United States and the International Criminal Court (ICC), as it has evolved historically, under the different past U.S. Administrations. The panel examined where the relationship stands today under the current Administration, the ICC’s Afghanistan Preliminary Examination and the ICC’s pending Preliminary Examination into Palestine/Israel and potential consequences for the U.S. The panelists included former U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes, Ambassador Stephen Rapp; Todd Buchwald, formerly Ambassador for Global Criminal Justice; John Washburn, American Coalition for the ICC; and Beth van Schaack, former Deputy to the Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues. Jennifer Trahan, Clinical Professor at NYU’s Center for Global Affairs, moderated the panel.

Background: The U.S. Constructive Engagement Policy with the ICC

Despite the fact that the United States is not a party to the Rome Statute, it had a constructive engagement policy with the ICC under the Obama Administration. This policy was adopted in light of the Bush administration’s retreat from its hostile stance with the Court, “recognizing that many of the United States’ most important allies were members of the court…and that the [C]ourt could serve U.S. interests and policy goals.

The Dodd Amendment was instrumental to this constructive engagement policy. In response to the Rome Statute that established the ICC in 2002, Congress passed the American Servicemembers’ Protection Act (“ASPA”) as “Congress feared that the ICC could be used to harass and detain American soldiers on foreign soil for purely political reasons.” Although ASPS constrained the US involvement with the Court, the Dodd Amendment (proposed by Senator Christopher Dodd), provides that “[n]othing in this title shall prohibit the United States from rendering assistance to international efforts to bring to justice Saddam Hussein, Slobodan Milosovic, Osama bin Laden, other members of Al Queda, leaders of Islamic Jihad, and other foreign nationals accused of genocide, war crimes or crimes against humanity.” In other words, the Dodd Amendment provided the US with a strategy of assisting the Court and other tribunals on a case by case basis.

Furthermore, under the Department of State’s War Crimes Rewards Program (“WCRP”), individuals who provide information regarding defendants charged with committing international crimes can receive rewards of up to $5 million USD. Legislation signed on January 15, 2013, and passed unanimously, expanded “the authority of the Department of State to provide rewards for information leading to the arrest or conviction in any country, or the transfer to or conviction by any international criminal tribunal, of any foreign national accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide.” The WCRP is another way the US is able to cooperate with the Court despite not being a signatory to the Rome Statute.

According to Beth Van Schaack, the request for assistance process was as follows: The Request for Assistance was initiated and transferred to the U.S. Embassy in The Hague, then to Office of Global Criminal Justice at the Department of State, to the Department of Justice which determined whether the request could be honored by the U.S. as per the ASPA and Dodd Amendment. If the request fell squarely within the Dodd Amendment, then it went through an interagency process (Department of State) to be determined as a policy matter whether the U.S. could provide assistance. Without including Israel, Palestine, and Afghanistan, the U.S. policy towards the Court was generally consistent and it did what it could to be helpful. It was a case-by-case basis process which determined whether there was enough U.S. interest in the matter and law. Now, there is a rejection of this concept no matter how much helping is in the U.S.’s interest.

U.S. Visa Ban on Fatou Bensouda

Nevertheless, the current Administration’s attitude and cooperation with the Court has taken a dramatic turn especially towards the ICC’s Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, a Gambian national. A point of contention is the Prosecutor’s 2017 request for authorization to investigate possible war crimes by American and Afghani forces in Afghanistan. For example, former National Security Adviser, John Bolton, threatened to impose sanctions and possibly criminally prosecute members of the Court as a result of this inquiry. More recently, Ms. Bensouda’s visa was revoked. The panelists expressed dismay at the U.S.’s actions and labeled the visa revocation as disastrous.

The United States should engage with Prosecutor and allow her to be even-handed, unbiased, soundly based and well-constructed; independent from the influence of the United States. More importantly, the United States should recognize that Ms. Bensouda has a lofty goal even if it objects to her process. Despite the visa revocation, Ms. Bensouda addressed the United Nations Security Council in May 2019 as “she was given a visa to travel to the U.N. for work, as required under the ‘host country agreement’ between the U.S. and the U.N.”

The ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber II’s Rejection of the Afghanistan Probe

As discussed above, one of the issues affecting the relationship between the United States and the Court is the Prosecutor’s October 2017 request to investigate alleged American war crimes in Afghanistan. “Her request said they allegedly ‘committed acts of torture, cruel treatment, outrages upon personal dignity, rape and sexual violence against conflict-related detainees in Afghanistan and other locations, principally in the 2003-2004 period.’” In April 2019, the Pre-Trial Chamber unanimously rejected the Prosecutor’s request to the dismay of human rights advocates, groups and victims of the alleged war crimes.

The Chamber listed multiple reasons for its rejection namely that the investigation would not be in the interest of justice to proceed; too much time had passed between the alleged crimes and the investigation; the availability of evidence from important people was unlikely to be preserved, and the fact that the authorities involved would be unlikely to cooperate and the Court’s limited resources. Advocates and the panelists took issue with the fact that the Chamber seemed to be influenced by political considerations; “changes within the relevant political landscape both in Afghanistan and in key States (both parties and non-parties to the Statute), coupled with the complexity and volatility of the political climate still surrounding the Afghan scenario.” Ambassador Rapp stated that the Court should not second guess Ms. Bensouda and should authorize the investigation of hard cases that help the rule of law.

Despite the Pre-Trial Chamber’s rejection, on September 17, 2019, it authorized Ms. Bensouda to appeal its decision to the Appeals Chamber. Ambassador Rapp also discussed the possibility of the U.S. using complementarity and investigating the alleged crimes in Afghanistan on its own. He suggested that the United States would have to use due diligence, appoint a special prosecutor and that it would have to be a genuine process.

Palestine’s Request for the ICC to Investigate the Israel/Palestine Situation

For the first time, Palestine referred a case to the ICC asking the Court to “open an immediate investigation into what it called Israeli crimes in the occupied Palestinian territories.” “The referral addressed a myriad of issues, ‘including settlement expansion, land grabs, illegal exploitation of natural resources, as well as the brutal and calculated targeting of unarmed protesters, particularly in the Gaza Strip.’” The panelists noted that there are complex issues implicated in this referral. First, Palestine’s statehood. Palestine is not a State, but it formally became a member of the ICC in April 2015 “giving the court jurisdiction over crimes committed in the territory since June 13, 2014 – including the 2014 Israeli assault on Gaza.” Second, the possible negative U.S. reaction if an investigation is started because of its strong support of Israel. Third, the possibility that Israel could argue complementarity; there is a strong argument that it has made efforts to ensure an independent process and exercised complementarity in prosecuting some of these crimes. Another is the challenging situation of settlements, and if this is a crime, that it has been a continuous crime since 1967.

What is the U.S.’s Public Attitude towards the Court?

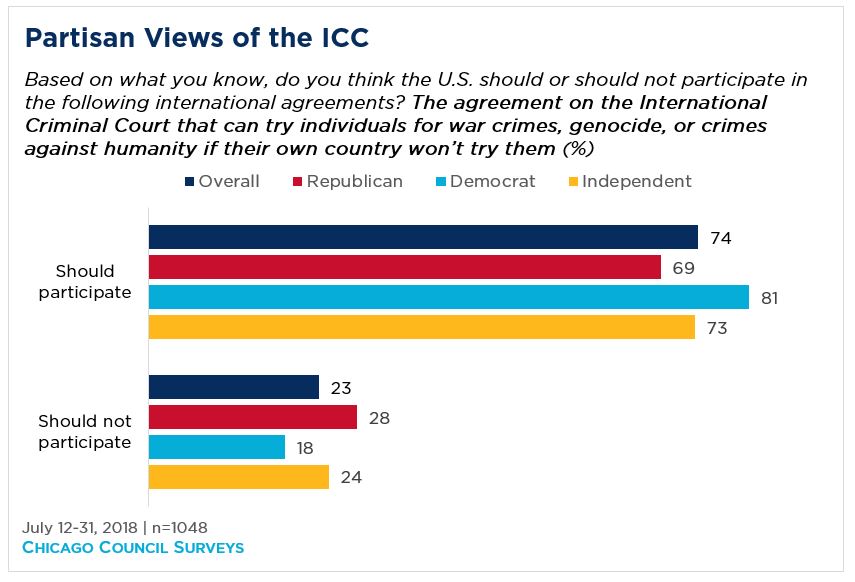

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs survey has been polling Americans on the ICC since 2002. Data from the new 2018 Chicago Council Survey, fielded July 12-31, 2018, finds that three in four Americans (74%) support US participation in the agreement on the International Criminal Court. That includes majorities of Republicans (69%), Democrats (81%), and Independents (73%).” The participants were asked “based on what you know, do you think the U.S. should or should not participate in the following international agreements? The agreement on the International Criminal Court that can try individuals for war crimes, genocide, or crimes against humanity if their own country won’t try them. Therefore, despite past and former administration’s attitudes towards the Court, “Americans have favored US participation. That support has held steady for the past sixteen years, with roughly seven in ten in support and between two and three in ten opposed.”

Conclusion

The panelists stated it was evident that the United States administration should engage with international tribunals, especially the ICC, like it has done in the past. Notwithstanding this fact, the ICC needs to change its mandate when it comes to its investigations and the countries it investigates; this is poisonous to the Court. Finally, the Court’s work is essential especially in this day and age. This work should be independent of politics, undisrupted and supported.