Last week Donald Trump took aim at the international economic order and the international institutions and alliances charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. This week’s post does not specifically focus on those policies; I am saving that discussion for later. Rather, given the urgency of the situation, it addresses briefly the “America First” element of his inaugural address, and its implementation via the current ban on all refugees and immigrants from 7 predominantly Muslim nations, one of several immigration-related Executive Orders released in the past week.

Charles Lindbergh speaking at an America First Committee rally

The “America First Committee” was established in 1940 to oppose U.S. entry into World War II. Isolationist sentiment reigned in the United States, and the thought of sending American youth back into harm’s way to save Britain and France was controversial. It dissolved after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 which made it clear that America’s isolationism was an unsuccessful effort to hide from the Axis war machine. What made the evocation of the slogan particularly chilling this time was that the America First brand was heavily tainted with anti-Semitism. Charles Lindbergh argued that those urging intervention were part of a Jewish plot to get America into the war against Hitler, and that influential Jews in the United States posed a great “danger to this country.” Trump’s invocation of that slogan is reportedly not new, and Trump himself denies the connection between the original group and his usage. But there are eerie parallels between the period prior to the beginning of World War II and today. It takes aim at religious minorities; it closes the borders at the same time as individuals fleeing persecution and atrocity crimes and aggression are increasing exponentially; and it relies on extravagant claims about the dangers individuals sharing a particular religion pose to the United States. The US Ambassador to the United Nations has already made veiled threats to countries disagreeing with the United States by noting in her remarks as she presented her credentials to UN Secretary-General António Guterres that the United States was “taking names,” a possible violation of Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibiting not only the use of force, but threatening force against the territorial integrity or political independence of UN member states.

![New US Ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, walks with other administration officials [via Twitter]](http://sites.law.wustl.edu/WashULaw/harris-lexlata/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2017/02/Nikki-Haley-and-Trump.jpg)

New US Ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, walks with other administration officials [via Twitter]

Although the Bush administration also used an Executive Order to establish military commissions at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility in 2001 to incarcerate foreigners it thought were threats to the United States, it was in response to the largest terrorist attack the United States had actually suffered just months earlier. The Trump Executive Order however, speculates about possible future threats to the United States and there have been no deadly terrorist attacks in the United States by any national of the 7 named countries targeted by the January 27th EO. This is similar in kind, if not in degree, to the run up to World War II, which involved extravagant claims by Hitler regarding looming threats to the German nation that were used as justification for war.

Trump’s Executive Order of January 27, 2017 fits within this gloomy narrative. In it, the President “proclaim[s] that the immigrant and non-immigrant entry into the United States of aliens” from 7 designated countries (Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Yemen) “would be detrimental to the interests of the United States and hereby suspend[s] their entry into the United States.” The order also directs the Secretary of State to suspend the US Refugee Admissions Program for 120 days, thereby halting all entry of refugees into the United States. Once refugee admissions resume, priority is to be given to those who make claims of religious-based persecution, “provided that the religion of the individual is a minority religion in the individual’s country of nationality,” which most observers read to mean a “Christian” minority religion based upon the countries included (although it could presumably include other minorities) and by statements made by Trump and his senior advisors.

Most commentary has centered upon whether the order is constitutional and in accordance with federal law, as well as a sensible policy likely to produce positive outcomes. Early responses to the order from within the United States and around the world have been extremely negative, with legal challenges mounting (and some succeeding) as individuals with valid entry documents, including visas and green cards, were stopped at airports outside of the United States and barred from traveling, or others were detained, often incommunicado or under stressful conditions, for long periods of time at airports while loved ones and lawyers tried to reach them.

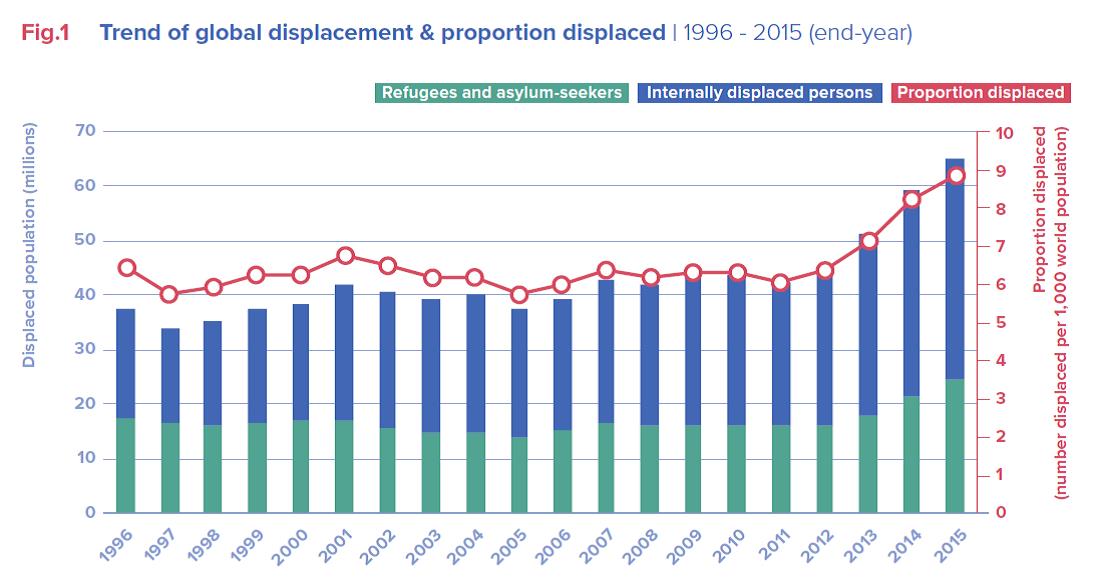

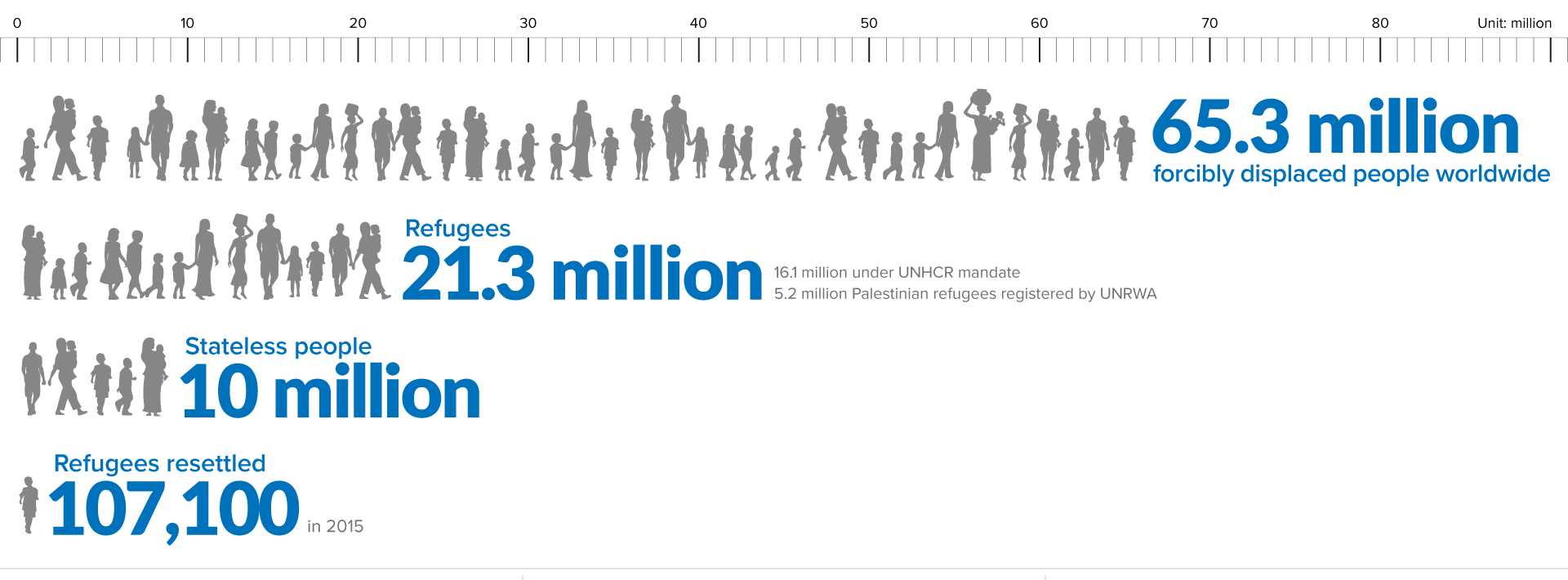

Source: UNHCR Figures at a Glance (2015 data)

This posting addresses the legality of the EO under international law and its impact on international relations of the United States. The ban arguably violates several treaties to which the United States is a party, including the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol thereto, which prohibit discrimination as to race, religion or country of origin and include the principle of non-refoulement, requiring states not to send individuals back to a country in which they would have a well-founded fear of persecution, and the 1987 Convention Against Torture, which prohibits torture under all circumstances and prohibits states from sending individuals to a country where there are substantial grounds to believe they would be in danger of being tortured. The United States ratified the 1967 Protocol (which incorporates the substantive provisions of the 1951 Convention) in 1988 with no substantive reservations or declarations, meaning that it is, under the US Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, the “Supreme Law of the Land.” It has also ratified the Convention against Torture. The EO may also violate provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a treaty that because it protects human rights, not just citizens’ rights, applies pursuant to Article 2(1) to aliens with or without legal documents “within [US] territory and subject to its jurisdiction.” Other important provisions include rights of fair treatment, of a hearing to establish the existence of a remedy, provisions on equality and non-discrimination, liberty and security of persons, the right not to be arbitrarily deprived from entering one’s own country (for green card holders), the rights of an alien not to be expelled without due process, etc. The United States ratified this treaty in 1992, but appended a Declaration to the effect that the treaty is “not self-executing” in the United States. The EO – and much of the media discussion surrounding it – may also violate provisions of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which the US ratified in 1994.

Possible legal and political responses at the international level for US violations include: retaliatory measures taken against Americans by countries upset with the new restrictions; censure before international bodies including the Human Rights Council, UN High Commissioner for Refugees Executive Committee, the Human Rights Committee, the Committee against Torture and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination; possibly voting Americans off important international institutions, treaty bodies and working groups; and simply not cooperating with the United States on issues important to it, ranging from telecommunications and cyber-security to rescuing US citizens in distress.

Domestically, it is difficult to enforce international law in US Courts. Although it may well be that the US “non-self-executing” reservation to the ICCPR is unlawful under international law, thus far American courts have been inclined to follow it, denying individuals standing to bring human rights claims directly in US courts. There have been cases brought under the Refugee Convention that have been adjudicated all the way to the Supreme Court, but the Court’s reading of the Convention has been narrow and in Sale v. Haitian Centers Council, the Supreme Court found that a presidential executive order turning back “aliens on the high seas” did not contravene Article 33 of the Refugee Convention as incorporated into US law. Another possibility with regard to the immigrant ban may lie with treaties of Amity and Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, which do not exist for the 7 countries currently covered by the EO except for Iraq, Iran and Yemen, but do exist with over 40 nations today, including many European countries, Latin American states and Japan. These treaties are self-executing and can support litigation in the United States for mistreatment of the foreign nationals they cover (see Asakura v. City of Seattle) and often have compromissory clauses granting international courts jurisdiction or providing other mechanisms of dispute resolution for individuals adversely affected.

The current EO applies not just to individuals without papers fleeing persecution but to individuals who have been already cleared for entry by the United States or qualified as refugees under the Convention. Moreover, there is an argument under human rights treaties and the Refugee Convention that the President’s duty under Article II of the Constitution to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” requires his compliance with international law, and particularly treaty obligations of the United States. While this understanding of the President’s constitutional powers may seem old-fashioned in light of the extraordinary expansion of Executive Power in the past few decades, perhaps it is time to recall the dangers that the framers saw in unchecked and unbalanced power. As Peter Shane writes, in Madison’s Nightmare: How Executive Power Threatens American Democracy, “it has become evident that Presidents, left relatively unchecked by dialogue with and accountability to the other two branches behave disastrously.” Perhaps it is time, as I have urged in other writings, to start taking international law and human rights seriously again.