By: Poli Rijos, Center Manager, Center for Community Health Partnership & Research; Gun Violence Initiative, Institute for Public Health

This blog is part of a special series by the Harris Institute’s Gun Violence and Human Rights Initiative and the Institute for Public Health’s Gun Violence Initiative in recognition of National Gun Violence Awareness Month, launched on June 5th for Gun Violence Awareness Day. Throughout this series we will highlight the work being done on this critical issue across campus, the St. Louis region, and the country.

This post originally appeared on Washington Universtiy’s Institute for Public Health blog.

In early June 2019, I spent eight days in El Salvador. Funding from the Institute for Public Health, the Episcopal Church of the Holy Communion, and my family gave me the opportunity to attend Global School by Cristosal. My assignment was to learn how to incorporate elements of the human rights-based approach into our public health approach to violence prevention. Luckily, I did not travel alone in this soul-searching expedition. I traveled with ten other St. Louis community members including clergy, Washington University in St. Louis and St. Louis University students, and one member from Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America. In El Salvador, we met eleven Salvadorian community members.

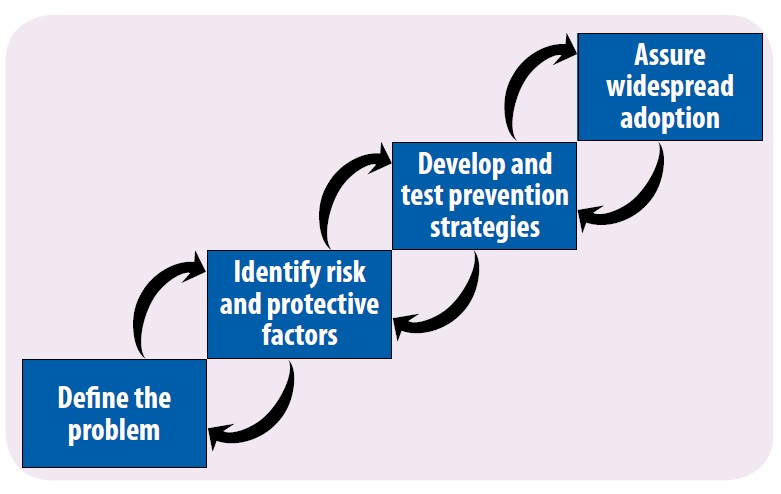

The seminar, entitled Community-based Peacebuilding: a response to violence with human rights approach, highlighted root causes and expressions of violence in different cultural contexts and how local communities, faith groups and government institutions can develop new strategies to prevent and address violence. Grounded in the United Nations’ Declaration on the Right to Development, Cristosal’s rights-based approach treats community partners as equal owners of their development process. Victims of violence are recognized “as subjects of rights rather than beneficiaries of goodwill, and defines poverty and violence reduction as a global responsibility.”Thus, Cristosal and community partners draft and build solutions collectively.

Why travel to El Salvador?

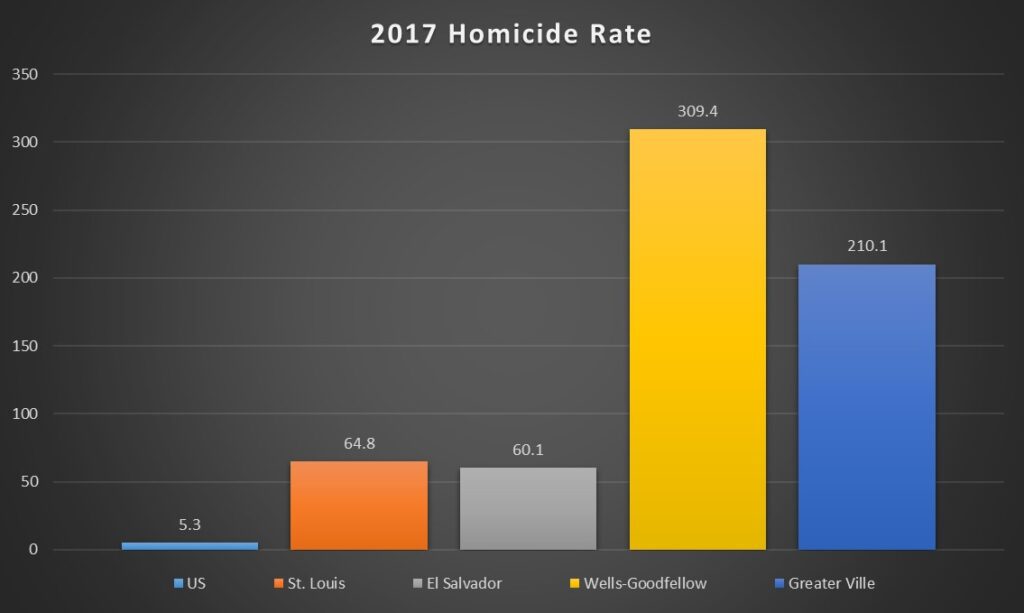

By working at the Institute for Public Health, I have learned that the terms global health, local health, and one health are deeply interwoven. The health of our citizens, animals, and environment are connected. In order to achieve optimal outcomes, community partners must guide our work, which must intersect and be collaborative. Thus, I am ready to learn from our siblings in El Salvador. Much to my surprise, some neighborhoods in St. Louis have higher rates of homicides when compared to El Salvador.

What does a combined peace-building model look like?

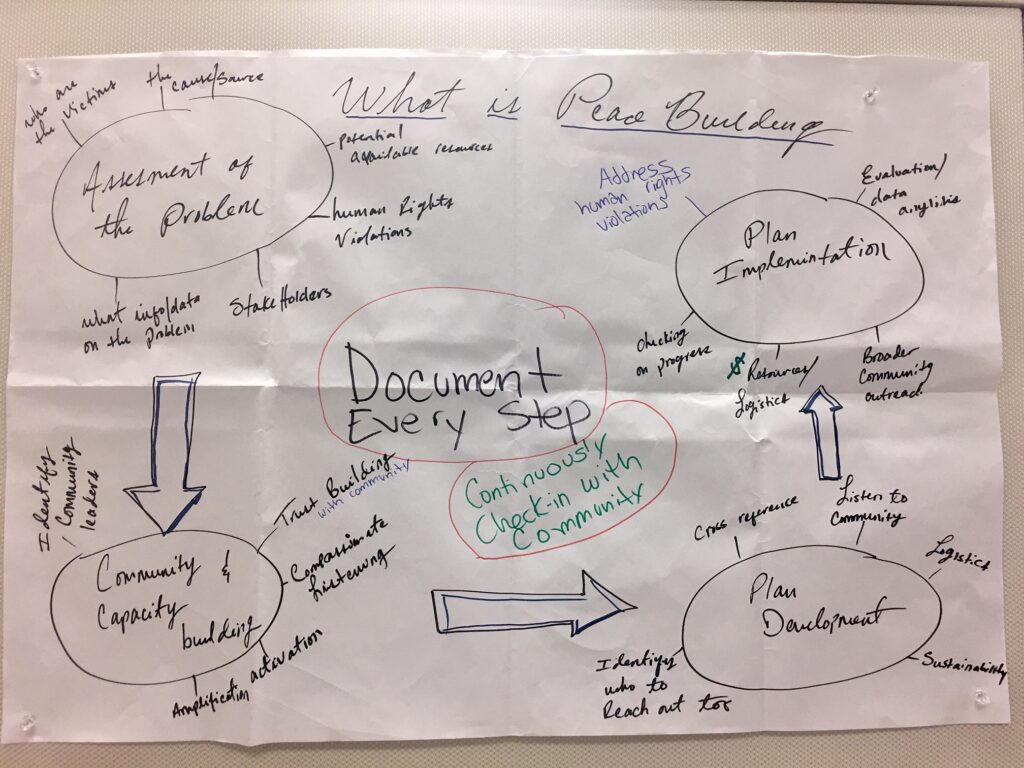

My Global School teammates and I defined “peacebuilding” as the process that empowers communities to solve issues like gun violence by centering their experiences. By combining elements from both the public health approach and the rights-based approach, we built a draft peacebuilding model that included: 1) assessment of the problem; 2) community and capacity building; 3) plan development and; 4) plan implementation that includes evaluation. Community partners must be included and consulted at all stages of the process. Finally, documentation of every step is vital to learn from successes and mistakes and to inform new stakeholders.

Final Reflection

El Salvador is more similar to St. Louis than I could have ever envisioned. Similar social determinants of health affect the well-being of our communities and similar human rights are violated. I am indebted to the Salvadorians who trusted us with incredible stories of pain, violence, trauma, but most importantly, resilience. I am back in my adopted home of St. Louis challenging my recent feelings of hopelessness and ready to deepen community partnerships. I must continue to center communities when developing violence prevention interventions. Now, I have a new and exciting challenge… add a human rights lens to my work.