By:

Hedwig Lee (Professor and Director, Department of Sociology; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity & Equity, Washington University in St. Louis);

Savannah Larimore (Postdoctoral Research Associate, Department of Sociology, Washington University in St. Louis)

David Cunningham (Professor and Chair of Sociology, Washington University in St. Louis)

This blog is part of a special series by the Harris Institute’s Gun Violence and Human Rights Initiative and the Institute for Public Health’s Gun Violence Initiative in recognition of National Gun Violence Awareness Month, launched on June 5th for Gun Violence Awareness Day. Throughout this series we will highlight the work being done on this critical issue across campus, the St. Louis region, and the country.

“The world is wrong. You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you, it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard. Not everything remembered is useful but it all comes from the world to be stored in you.”

— Claudia Rankine (Citizen: An American Lyric, p. 63)

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into full-frame the devastating consequences of racist practice, both in its contemporary and historical forms. Gun violence likewise has wreaked havoc within communities of color in the US, its stubborn persistence extending beyond even the most dire predictions around the length of the pandemic. As Claudia Rankine’s poem suggests, these diseases are inextricably connected, both driven by structural racism.

As Zinzi Bailey and her colleagues explain, structural racism “refers to the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination, through mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, and so on) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.” These inequitable systems work in tandem to produce, maintain, and reinforce inequalities in health.

Social scientists have shown that a history of racial violence, along with current racist policies and practices that reinforce this history, serve as fundamental causes of the health disparities that disproportionately impact African Americans and other communities of color today. In the U.S. over 15,000 children and teens are shot and injured each year. A fifth of those victims are killed. Firearms take the lives of 10 times more Black children than white children, serving as the leading cause of death for Black children.

These stark realities define a human rights crisis that has been highlighted by numerous international bodies. Just last week, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelete referenced how “COVID-19 exposes glaring inequalities in [the U.S.], show[ing] why far-reaching reforms and inclusive dialogue are needed there to break the cycle of impunity for unlawful killings by police and racial bias in policing.” This conclusion builds on earlier UN findings criticizing the lack of gun control and the presence of stand-your-ground laws. Similarly, in 2014 the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern around “the high number of gun-related deaths and injuries which disproportionately affect members of racial and ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans.”

This racial stratification of violence is rooted in decades of policy that has systematically marginalized communities of color. High rates of residential segregation, for example, stem from histories of racist housing practices — including racial covenants, redlining, and other discriminatory mortgage practices — that, in turn, have limited access to employment and educational opportunities, as well as social services and medical care that buffer communities from gun violence. Yet at the same time, legal remedies for civil rights violations, including in housing, employment, and education, have been rolled back since the early 1980s. Recent social science research also has linked physical violence against African Americans, as reflected in terrible histories of lynching and racial pogroms, to present-day homicide and gun violence.

Experiences of gun violence and its many negative consequences are further amplified due to the lack of resources in place in these segregated communities to help individuals and communities cope with and heal from associated trauma. Moreover, biased media portrayals exaggerate levels of gun violence and reinforce negative stereotypes of communities of color, further compounding inequality and disinvestment in racially segregated communities.

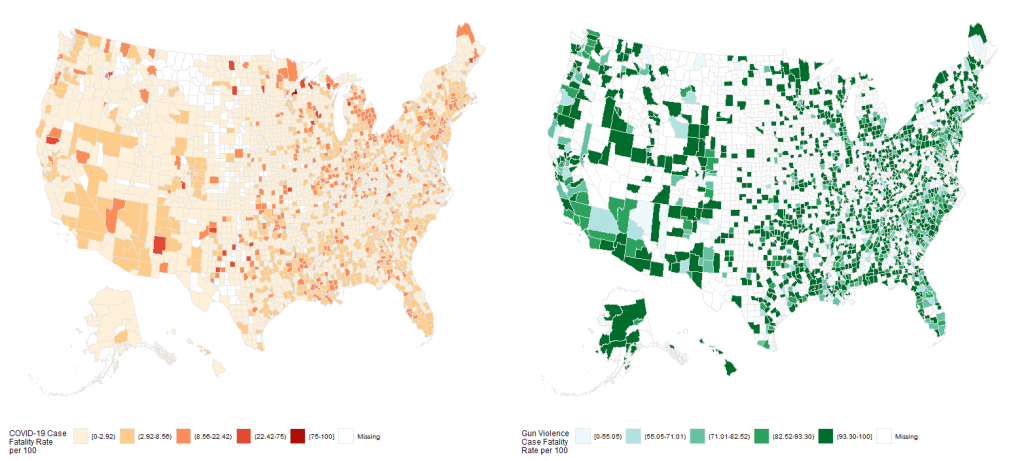

Some of the very same racially-biased practices and policies have also served to increase COVID-19 infection risk and deaths due to infection. In fact, as we can see with these two maps of the US, the same areas where people are dying of COVID-19 at disproportionate rates are some of the same places we see the highest levels of gun violence death. Mutually tethered to structurally racist systems that serve to maintain racial inequality in all its forms, these patterns exist by design.

Figure 1. Case Fatality Rates by County for COVID-19 (left) and Gun Violence (right). Case fatality rates show the number of deaths due to COVID-19 or gun violence relative to the total number of COVID-19 or gun violence cases, respectively, per 100 residents. COVID-19 data are from the New York Times and gun violence data are from the Guardian (originally sourced from the Gun Violence Archive, 2015 data). Legend categories were identified using the Fisher breaks algorithm.

While often difficult for academics, medical practitioners, scientists, policymakers, journalists, elected officials, and others who help define and respond to public discourse to do, we must name structural racism as a source of inequalities in gun violence as well as other health conditions. Racism is itself a violation of the human right to be free from discrimination, which in turn fuels other violations, including those associated with access to the rights to health and education. As such, under international law, the U.S. government has an affirmative obligation to prevent its commission. Because racism is literally killing us.