By: Isaac Amon

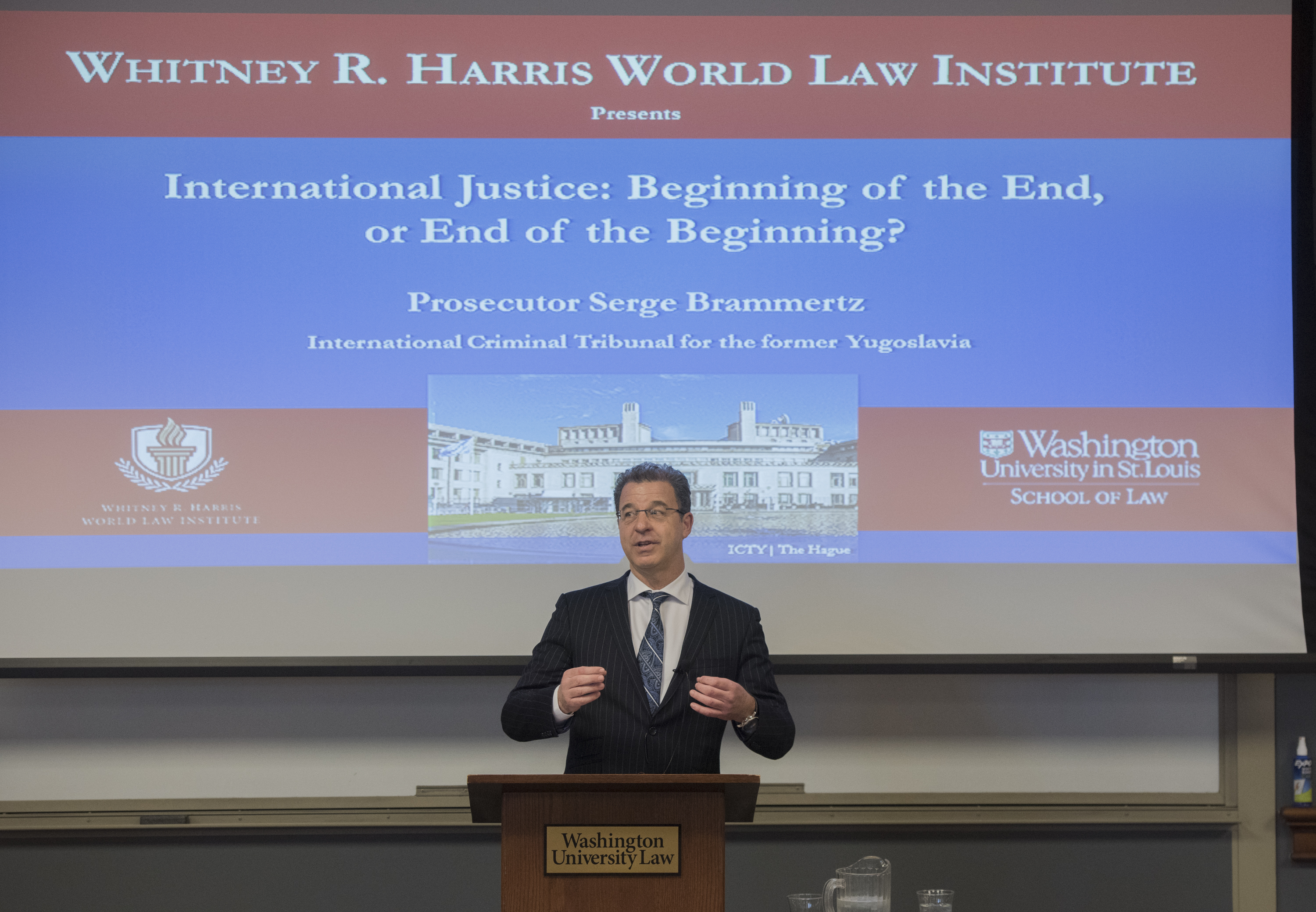

Chief Prosecutor Serge Brammertz of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) recently delivered a lecture at Washington University School of Law, International Justice: Beginning of the End or End of the Beginning? He recounted how modern international criminal law was formed over two decades ago with the establishment of the ICTY in 1993. Faced with the worst crimes committed on European soil since the Holocaust, the United Nations Security Council created the international tribunal. It was modeled after the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which tried the highest ranking Nazi defendants for war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes against peace (referred to as the crime of aggression today).

The ICTY will complete its mandate within two years, and close its doors by the end of 2017. Over the past 22 years, the Tribunal has changed the landscape of international humanitarian law and conflict resolution and produced precedent-setting decisions on genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Its experience has influenced the creation and proceedings of other international tribunals, including the International Criminal Court (ICC). According to the Prosecutor, both legal as well as political lessons were learned from the ICTY. When the Tribunal was established, many indictees remained at large and there was a lack of political support from countries of the former Yugoslavia. However all 161 indictees have been caught and the ICTY is the only tribunal that has no remaining fugitives.

Prosecutor Brammertz credited two factors for this turn-around: (1) the support of the United States government, which supported the tribunal financially and logistically from the outset, and (2) the conditionality policy of the European Union. The European Union mandated that a precursor to membership was full cooperation with the tribunal, particularly in locating and turning over fugitives. At the time, this political push made a significant impact, as many states from the former Yugoslavia were vying to enter the EU.

Prosecutor Brammertz then spoke to the importance of capacity building in all conflict zones including ICC countries and used his experiences at the ICTY as an example. The Tribunal worked to ensure greater cooperation between countries and between the Tribunal and national justice systems. The ICTY’s database of over 10 million documents, which is available to national prosecutors, has been utilized in national and local prosecutions, and local prosecutors have been integrated into the ICTY as well.

The Prosecutor also shared his lessons learned in regards to the scope of an indictment. In its early years, the ICTY detailed too many crimes in indictments, which were timely, costly and allowed the case to get bogged down in details, whereas indictments at the ICC are very limited and often cannot represent each situation in its entirety. If the indictment is too encumbered, it can detract from the overall picture and be redundant; but if an indictment is very short this may place too much responsibility upon witnesses. Thus, a middle ground must be found in this important area.

As the age of the ad hoc tribunals comes to an end, only the ICC will remain. The ICC, according to the Prosecutor, should focus upon national capacity building and should have a completion strategy for each situation. It cannot prosecute every crime and every perpetrator. Consequently, the ICC must selectively prosecute each case and enable the national system to handle the rest.

Prosecutor Brammertz concluded by saying that it is the beginning of the end. Two decades ago, a sense of idealism prevailed and a strong belief existed that international institutions could bring justice to victims of atrocities. However, as the course of the past two decades has shown, it cannot stop atrocities from occurring around the world. Thus, it is also the end of the beginning, in that the international community has learned lessons and has developed alternative institutions to combat impunity. The reality is that international justice can no longer be the sole accountability mechanism to bring perpetrators to justice, and justice to victims. Rather, national and local capacity building, especially in the increasingly important area of forensic evidence, must be bolstered by the international community. In the end, justice at these levels simply cannot be replaced, for they will be responsible for performing this incredibly important role, and for combating the omnipresent threat of impunity.