By Megan Ferguson

Part 1 of 2

Asserting that international law matters seems particularly vital in 2018. In the United States, reactionary and nationalist voices are currently most amplified to the general public; international organizations and agreements are examined with a realist distrust, which in turn leaves both States and organizations uncertain about America’s commitment to its obligations or even the current international system. So, asking, “does international law matter” at the 2018 International Law Weekend is more than a search for validation from like-minded practitioners; it is an essential query with plenty of room for academic dissent. Still, consistent throughout the weekend was one repeated theme: there remains hope for international law’s importance and its broader impact on individual lives.

The panel, “The Meaning of Torture in National Security,” demonstrated a hope that even when States violate humanitarian law, individuals may hold the State accountable, or even create change from the ground-up. However, encouraging individuals to do so first requires tackling misconceptions in America’s popular views of torture, especially during an age with President Trump says torture works and that he supports it.

2002 Torture Memo

The Central Intelligence Agency (C.I.A.) uses very specific, calculated, and “tried-and-true” torture methods, said Amrit Singh, Counsel & Head of the Accountability, Liberty and Transparency cluster at the Open Society Justice Initiative. These methods include employing stress positions, disrupting sleep and waterboarding; some of these methods may even cause pain “equivalent to organ failure,” Singh said. These methods of torture have been used in Iraq and Afghanistan with direct government oversight and recording. A 2002 memo even explicitly authorized the methods’ use on detainees held in Guantanamo Bay.

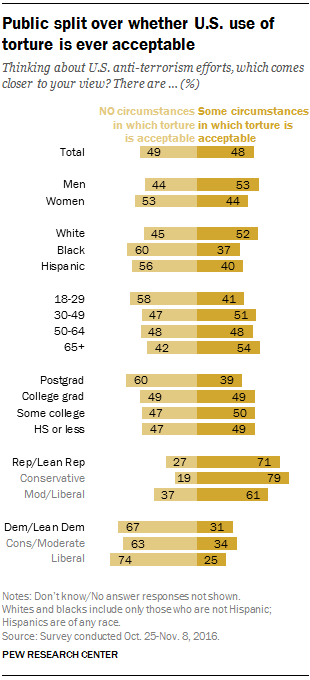

Still, the American public largely believes torture is “not systemic,” Singh said. Furthermore, approximately 48% of Americans support the use of torture without context. When asked whether torture is necessary to obtain intelligence on terrorism, that number increases to 63% of Americans, according to data from 2014, displayed in the chart below, and 2016.

The demographic breakdown of Americans’ support for torture shows a near-even split. Gender, race, and age, as well as political party, all correlate with support for torture.

However, the use of torture is not correlated with obtaining actionable intelligence. Instead, information obtained from torture is responsible for some of America’s most famous instances of false intelligence, including information on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), said Dr. Margaret Satterthwaite, Director of the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice Clinic at the New York University School of Law. This demonstrates the “massive consequences of human rights abuses on a micro-level,” said Singh.

The government may be largely responsible for this misunderstanding. In order to “get ahead of a Senate report” which was about to demonstrate that torture was not responsible for obtaining actionable intelligence on the location of Osama Bin Laden leading up to his 2010 capture, the CIA shared confidential information on the torture of a client of Alka Pradhan, Human Rights counsel for the Military Commissions Defense Organization, with the producers and directors of the movie “Zero Dark Thirty,” said Pradhan.

The portrayal of torture and the implication that this torture was necessary to capture Bin Laden helped the American public feel comfortable with torture as a policy so long as it is used to obtain information from a clear “other.” It is “necessary to dehumanize,” explains Satterwaite, who further said that the government uses “very explicit Islamophobic grounding” when discussing torture and its necessity.

Finally, even when confronted with torture’s systemic use and ineffectiveness, the “dominant white public wants to say, ‘that’s not so bad’” said Satterwaite. “It’s like a friend who watches the Olympics and says, ‘I could do that.’”

Any attempt at change should combat these misunderstandings surrounding torture’s severity and use. Support for torture is largely split along party lines in the United States. Encouraging change on an individual level will therefore require presenting information in a manner which does not challenge political identity; otherwise, that information will not be viewed as good policy information, but as a partisan threat. When viewed through this lens, Americans may be more likely to support torture, even if they did not hold a strong opinion on it before being presented with that information. When presenting true information on whether or not torture is effective, it will be necessary to avoid blaming a person for previously not thinking this and to avoid blaming the government for torture, even though the responsibility for the practice lies with the State. Both practices are essential for encouraging a person to fairly analyze torture as a policy without feeling personally threatened by the implication their particular political party may be involved in something immoral. These practices are especially important to creating change in the United States’ torture policy.

Torture can only end through “democratic politics. The people must demonstrate their will,” said Saitherwaitte.